|

The Elephant Man is one of those films that leaves you wondering long after you've watched it. But you may be thinking that this is no surprise, since it was directed by David Lynch -- a creator of perplexingly ambiguous worlds and dreamlike situations who maliciously grimaces at the thought of baffling his audience with all the inexplicability. Yet, that's not the thing. Once you watch The Elephant Man you will most likely not be confused or bewildered -- you won't be asking yourself, "What the heck was that?" No. Rather, you will be royally touched, because this is a film whose regard for human decency is extremely powerful, and even now, moving.

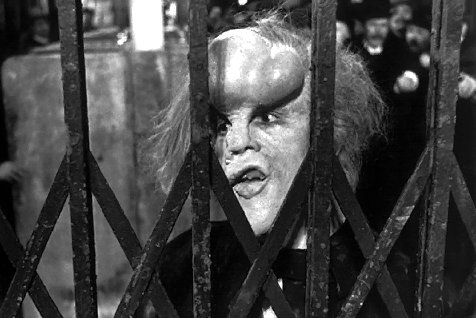

It is mighty clear that when making this film, Lynch did not lose touch of his out-of-this-world strangeness. There are some moments of blackened weirdness, but all in all, these have been toned down. The circus world, which includes bearded ladies, giants and yes, dwarfs, seems to have been pulled straight out of Lynch's mind. Because that's what its full of: bizarreness, incomprehensibility and mystery. However, in contrast with his debut, Eraserhead, the story is very easy to understand above all, it is straightforward. John Merrick [splendidly played by John Hurt] is severely deformed at birth by a rare disease. On account of his abnormality, he is known as "The Elephant Man". His grossly disfigured countenance manifests the features of an elephant. Trapped in a nomadic freak show, Merrick suffers the torment of an outcast from society every day, and when people come and see him, they're both repelled yet ineffably attracted; also, his master brutally beats him on a frequent basis. Not long afterwards a young surgeon named Dr. Frederick Treves [Anthony Hopkins] rescues him and provides him with shelter in one of London's hospitals. The tale unravels as Treves discovers that beneath Merrick's monstrous fašade lies a gentle and peaceful man.

The Elephant Man is a wonderful film. Most of its effectiveness is due to the fact that, more often than not, it decides to suggest instead of merely showing. Its subtlety is one of its most pivotal elements and it works rather greatly. In one of its most impressive scenes, when Dr. Treves first sees The Elephant Man, the camera zooms in on him and he sheds two tears. What he has just seen is something deeply amazing, yet somewhat sickening -- he's never seen anything like it. The look on Treves' face is one of awe and grief; we know what he's thinking despite the fact [and here's where the greatness of it all lies] that we, as an audience, have not yet seen The Elephant Man. Be it terror or sadness, Treves is profoundly affected by this encounter. David Lynch gives us a glimpse of Merrick from then on [during an anatomy lecture in front of a group of scientists, where we only see his shadow projected on a curtain, for example], but does not decide to show him in his entirety until some time later, thus heightening our anxiety for seeing this so called... freak. Once we do see him, however, we, like the characters before, are both shocked, yet ineffably captivated.

Dignity is a word normally used to describe what this film is about. To some extent, it certainly is, but there is much more than that. Lynch not only chooses to illustrate Merrick's state as a human being, as he also opts to tell us how his unlikely friendship with Dr. Treves gradually blooms. At first, Merrick seems to be an unintelligent person. He does not seem to be able to talk, but when Dr. Treves finally persuades him to mumble a few words, he does. By this method of repetition Dr Treves teaches him how to speak slightly, and in order to impress his superior, he tells him what to say when they both meet. The superior asks Merrick some questions which he had not planned, and he answers them all with the same words, "Pleased to meet you". Later on, however, Merrick is heard reciting a prayer, all on his own, and thus they find out that he's smarter than they thought. Dr Treves introduces Merrick to his wife, and he's startled by her uncommon beauty; something which he, regardless of what he does, will never have. Juxtapositions of themes, both superficial and innate, can be found in the film wherever you look. The film deals with Merrick's re-awakening, in many senses; had he not been born in such a way, he would have been of a middle-upper class, which is the indication that we obtain when looking at his mother's picture that he always has -- a woman both beautiful and fragile -- and you may wonder, how could someone like that give way to such a monstrous creature? Merrick has been isolated for most of his life. Having been bullied, beaten and exploited for a very long time, Dr Treves' rescue proves to be an abrupt yet extremely appropriate event, as Merrick finds the true wonder of living the way it should be done. People respect him and value him for what he is [just like themselves]: a human being. It's as though Merrick has been reborn; but it is not long until Dr Treves finds out that, by showing him to everyone and having news about him every day on the papers, he's doing what the others used to do to him: exploitation. That is yet another of the main contrasts, if you will, of The Elephant Man; Treves wants to get to know Merrick properly, but in doing so, a lot of emotions cross his mind, and thus somewhat distort it, whereas Merrick, as the course of the film goes on, makes amends with himself and men, while feeling more peaceful inwardly. Merrick may be utterly destroyed on the outside, but it is Treves who, despite his outwardly well-being, suffers the most trouble. "And you've done so much for me", Treves tells Merrick. That line he murmurs, with a penetrating vagueness, and it is not clear what he really means. It's no coincidence that Merrick is the person depicted with the most humanity of the film.

Lynch's story is set in Victorian London, and as such we see both the good sides of it and the bad sides of it. Every once in a while, the camera focuses on the wafting smoke that the factories produce, on the constant rambling of the machines -- once it even shows us the victim of a machinery accident who is being operated by Treves. Lynch is clearly communicating to us that industrialism -- that reproachable, grotesque thing -- is slowly taking over and wiping out the beauty of the world. Beauty is not just something which corresponds to human beings, which is why we're shown this, because it's not just us who can be ugly [or otherwise]. Freddie Francis' sublime cinematography portrays London as a nightmarish and dirty world, where, surprisingly, good things can occur, too. It's reminiscent of films such as Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast, mainly due to its odd abstractness and stark contrasts of light and dark.

Devoid of any cheap sentimentalism, the film is magnificently directed by Lynch, who tells it with the utmost sincerity. In his own words, while referring to the title character, Lynch has said that "he is this beautiful soul trapped in this horrible body and that's what the whole film is about". Indeed. Lynch illustrates the film as a nihilistic nightmare, full of German-like expressionism in its images and containing an overwhelmingly sinister atmosphere -- and all these contrast with the basic message of the film. Fantastically acted by Anthony Hopkins, John Hurt and the like, the film has a Dickens-like ambiance to it all, and its set pieces, costume designs and whatnot are all very finely done.

John Merrick never speaks for himself until the end. When he cries the unforgettable lines "I am not an animal! I am a human being! I am a man!" we know that all the excruciating pain he had gone through had been suffered in silence. Though somewhat uplifting, the film still makes you feel bad, one way or another, because one cannot help but think that we, if there was such a person before us, would act cruelly towards them. The fake cathedral that he constructs represents the world that he's immersed himself in -- a world within the real world. It is Lynch's obsession with alternate realities or hidden places that lurks around this film, and his eye for dream-like situations is also present here. The ending scenes say a lot to us and basically fold everything that had been told to us in a nice little package, and the last image of the stars, like he would do again in the terrific The Straight Story, indicates that there is a world beyond this one, for every one of us. Burning with humanity and visionary mastery, The Elephant Man is, ultimately, a tale of courage and reprehension, two themes that, aided by Lynch's ever-observing eye, prove to be the foundations for a glorious film indeed.

[94]

|